Follow technology dream, slightly un-break the world , accept some regret

Over 15 years , I made a few sacrifices to follow my tech dream to make the world slightly better place. After 4 years of reflection, I have some satisfaction and some selfish regrets. Click bait but true, the selfish regrets probably aren't what you'd think.

DISCLAIMER: There are at least 20 people I don't

acknowledge here. Without you accepting the legal

responsibility of board membership, making generous,

sometimes sacrificial contributions of resources and/or

providing the political and fund-raising advice I needed

to keep our nose above water, this work wouldn't have

happened. You deserve acknowledgement. However, I took 3

years to write what is here. Any more delay and this note

will never be finished. I hope you know who you are and know

that that I am grateful for your help.

Confirmation bias is a thing. If you repeat, over and over: "At least I tried", you can tell yourself: "yes, it was worth it."

If you believe:

"Do not store up for yourselves treasures on earth, where moth

and rust destroy, and where thieves break in and steal. But

store up for yourselves treasures in heaven, where neither

moth nor rust destroys, and where thieves do not break in

or steal; for where your treasure is, there your heart

will be also.

...Earning about $7,000 per year for 15 years of tech support, system

administration, cat herding, tutoring and software engineering is just

fine.

So that's me with a spouse that paid the rent so I could be

holier-than-thou for 15 years. Compared to the quiet guy

who has run a good after school program in the same notorious low

income neighbourhood for 40 years, I have few, legitimate self-righteous

points.

Not maximizing my income was a means to the end of my dream of

using technology to make a better world at the

Community Software Lab (RIP).

However, being (somewhat) low income had interesting side benefits.

For example, these last 4 years at market rate, our income more than

doubled. However, it ***feels*** like we've only been living only

slightly large. Dinner and drinks a few times a week vs just coffee at

the local shop. Running outside in the winter vs Yoga 5 days a week.

Perhaps, the feeling of living large these past 4 years is muted by paying debts

and starting to save toward old age.

Again, confirmation bias, but past an income floor of < some number of $ >, limiting desires is probably a better strategy for material happiness than increasing income. We still have credit card debt, but instead of paying to attend funerals on the other side of the country, we're paying off a winter

beach vacation.

In my limited experience, subjective perception is better predictor of satisfaction than empirical measurement. Surrounded by middle income family, acquaintances and in-laws the expectations of our peers was always a greater pressure than the cost of adequate housing, food or medical care.

When I was a practising Catholic, I did informal tech support for the

Oblates of Mary Immaculate. If lunch-time came in the middle of work,

we had lunch together. I have a sense for how these guys live. Everyone

has health care, an allowance for new uniforms, meals, a computer a bed

room and a bathroom to themselves and a spot in the retirement home

when the time comes.

The rooms were a little smaller than your average Motel 6, but a little

less shabby. I think they got $20 per week in spending money. If they

needed a car for work they submitted a budget. Oblates working over

seas live even simpler, closer to the people they serve.

The Oblates have infrastructure and a supporting culture. It didn't

seem like honouring the Oblate vow of poverty was a significant

struggle. My spouse and I struggled in our unstructured time of relatively

simple living. I think our struggle was more about

being embedded in the culture of money than it was being able to pay our bills.

Considering only the money issues, for at least me, autonomy and the

chance to make a difference, were worth not maximizing our income.

However, for different selfish reasons, given a do over, I would do

things differently.

The last 8 of 15 years, my focus was using novice programmers to build

useful software for low income people in a organization I started

called the Community Software Lab. Three lab alumni work at Google, Amazon

and Microsoft. More significantly, three different people explicitly

credit the Community Software Lab for significantly better opportunities

and lives than they would have had otherwise.

Despite occasional flashes of student brilliance and the many personal

indulgences granted me by teachers and educational bureaucrats, I've

long considered the industrial/educational complex ineffective and

unjust. The lecture system was created in medieval times because it is

quicker to read a book aloud to 50 people than it is to hand-write 50

copies. Adjunct professors do almost all the revenue producing

teaching but those without independent means are eligible for public assistance.

(about 25% of them)

Writing software that people use, following a modern process is a better way

to learn to program than listening to lectures or copying your

roommate's homework. Requiring 100% test coverage for new code, creating detailed

engineering documentation, tools , standards and processes and (most

important) re-re-doing line by line code review, allowed people

starting with only the ability to write a FOREACH loop to contribute

production code and gain real skill. By unanimous testimonial, working

with me was hugely more educational than undergraduate computer science

education.

This is all anecdotal, but I challenge any CS dept to provide better

outcomes with their standard program than I could locked in a room with

five CS 101 grads and their tuition for 4 years.

The problem is that most people don't have the drive to write software.

They want a paycheck or the entitlements accorded to the coder caste.

They don't want to stay up until 3:00am, failing again and again,

debugging for joy or compulsion. I helped hundreds of people confirm

that they really didn't want to be engineers. The educational industrial

complex has the advantage of not investing much emotional energy helping people accept their failure.

Over 8 years, of the approximately 200 people who I setup development

environments for, 10 people created more value (useful code) than I

could have created by spending the setup/ tutoring/ code review time

just writing code myself. More people personally benefited from the experience,

than contributed more than they took, but wasn't the greatest good for the

greatest number.

Given only 1 chance to repeat the last 8 years of volunteer experience,

(previous 7 are another matter) I'd ignore everyone else and lock

myself in a room to code. Crappy as it was, our software did refer tens

of thousands of people to the social services they needed. Not-crappy

software would have been a far greater good for a far greater number.

Certainly more the (at best ) 25 people who got to be better

coders from their work with the Lab.

Compounding the uncertainty is my suspicion that most of our

"successful" alumni would have made it anyway. The MIT dropout, yes.

The guy with 10 years industry experience waiting out a recession, yes.

The driven, angry, smart kid who'd lived half his life in foster

care, probably.

Despite our best efforts, most of the people we gave practical

experience to weren't especially dis-advantaged. Our usual admissions

test was "Use Javascript to prompt the user for a positive integer,

print the numbers between 1 and that integer". In theory this bar is

low enough for anyone pass, in practice only 2 of the 10 productive

people came from a low income background or with a label like "at risk

youth" We probably accepted a good number of people without advantages, but

subjectively, the big service we provided most of them was helping them accept

that they didn't like coding.

Selfishly, given 8 years of effort, I wouldn't be the mediocre

programmer I am today. If instead of explaining the same things over

and over, I'd written and re-written code, I'd be pretty good, or at

least better. It felt horrible to blow the recruiter level phone screen

at Facebook. It felt worse to be completely oblivious to the sql INNER

JOIN syntax on a web dev interview for a spot on a team full of people

as smart or smarter than me. (FWIW, I am still reasonably employable at

a few levels below elite. )

In both interviews, I missed things because I'd been focused on explaining

existing code and making it hard for people to screw up new code instead of

writing new code or updating code myself. Building skill is a different

than helping other people learn. Also, usually being the most knowledgeable person in the room is not a recipe for personal growth.

For example in 2006, it was an acceptable practice to connect database tables in the SELECT clause. By my interview in 2013, modern databases supported JOINs and modern programmers used them.

This strong regret was obvious only in hind-sight, after I'd been away

from the lab for a few years. In the moment, it was mostly great. I

like Yoga a lot partly because the instructor usually feels compelled

to thank the class for the privilege of sharing the skill. It feels

very, very good to contribute to other people's ah-ha moments.

People talk about engineering education a lot like they talk about

baseball. At the little league level there is lots of fun, but

eventually the grind sets in. Maybe the grind is the price of

greatness. Maybe the grind is yet another black mark for the

educational/industrial complex. Having 3 people get jobs at famous

companies, was OK. More satisfying than alumni success was watching

a women, a serious A+ student, pound her heels, shake her fists

and giggle after fixing a complicated bug.

Overall, these moments of joy didn't add up to what might have been

with a more selfish approach.

--- or maybe a more effective approach ?

It's kinda obvious, but the reason only about 10 people gave more than

they took and (guessing) only about 25 people benefited from the

practical experience was that not many people put the needed time in.

Without exception, people who dabbled, trying to fit our work in

between school or other jobs or being a mom, were a net loss. Some of

those people were quite talented but just couldn't find the time.

The people that succeeded put in at least 20 hours a week and most of

those people got paid a small stipend, --Often below minimum wage, but

something.

Most of the people who succeeded, were Americorps/VISTAs, The government

paid them 16K per year and basic health benefits. The program was created by

President Kennedy to fight poverty through (almost) voluntarism and

required a full time commitment. Other people got funded through Google

Summer of Code. We got some contracts. I was able to fund-raise to pay

other people. I did other completely unrelated contract programming

work that paid relatively well.

This is an insight for other groups trying to skill-up low income or

disadvantaged people. "Work for free" is not perceived as a survival

skill by low income people or entitled feeling middle class people.

There is an almost infinite distance between "almost nothing" and "free"

for both producers and consumers. Many people needed the stipend to pay

their rent. Other people just felt exploited working for free ---Even

if the "work" was mostly training that they'd otherwise have to pay for.

The ideal would have been to have a summer camp with computers ,

Internet access, showers, a silo of rice and a silo of beans. Given

that I spent about half my time trying to fund-raise as a charity and

barely kept the doors open with an annual budget of around 20K , this

was probably not a reachable ideal.

Given more than (1) chance for a do-over, I might just have worked as a

market rate programmer, banked the money for 8 years and retired early

to spend the banked money on stipends. ( Assuming my wants didn't

expand to match my earnings )

The biggest sacrifice wasn't money, but personal growth. The biggest

barrier to most people's personal growth was a little money. There is

a difference between something and nothing. So there it is. Money isn't

important, except when it is.

I've covered the major regret ( lack of personal growth). A minor regret is lack of measurement. If I'd taken the time to better define success in advance, I might have changed course earlier and I might have fewer doubts now

Disclaimer:

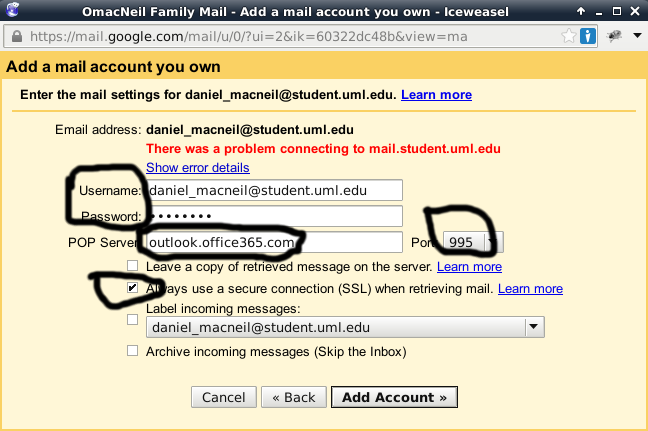

The first version of our (MVHub) software was written by DS and EA in about 8 months working by themselves. During their work I was mostly focused on system administration. ---providing email,

web hosting and databases to non-profit organizations.